broken open by an 8-hour layover

on the virtues of being a museum weirdo

It was 10 am when I arrived at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and I’d been awake for nine hours. My flight to Los Angeles left at 6; my eyes were puffed-up and scratchy; my phone was at 26%. I was about three flat whites away from collapsing into kangaroo feed, with greasy hair braided into obedience and two fresh bruises blooming on my kneecaps. The courtyard was filled with millennial parents and their sticky Australian children. Three banners with stern-looking women hung over pink-marble stairs. I couldn’t tell if the tropical birds were scowling at me or if their faces were just stuck that way.

I was on the tail end of an odd and tiring vacation through Australia and New Zealand, which I’d mostly used to berate myself for my recent creative failures. Stimulation has been easy to find in New York; inspiration less so, and the time to act on it even lesser. My writing has collapsed under the weight of expectation, comparison, and the lamentable need to do well at a job that actually pays, and my resulting output’s been weak, when it exists at all. A growing body of evidence suggests that there is no sturdy professional path for the work I want to do — any level of success or even stability will only come from a remarkable combination of scrappiness and luck. I was deflated, disconnected, burnt out on trying.

With that particular black cloud hanging over my head, I wasn’t sure what the museum could offer, other than a place to stand for a few hours. But I had a 15-hour flight and, I guess, the rest of my life ahead of me. The fine white static that had replaced my internal monologue seemed to approve of the idea. I ducked around the angry birds, entered, and bought a ticket to the limited exhibition: “Dangerously Modern: Australian Women Artists in Europe 1890-1940.” The cashier asked for my postal code and I gave it, which left us both confused. I descended three escalators and blinked hard. My eyes felt like sandpaper.

I came late to museums, generally speaking. They felt like a chore until about three years ago, when I arrived early and alone at the Rijksmuseum on a November morning and was whacked over the head (figuratively speaking) by an oddly-framed painting of a sad little monk.

The piece is unremarkable, academically speaking; its placement in the general “Romanticism” gallery, far from the Vermeers and Rembrandts, was evidence of that. Its painter, Frederik Marinus Kruseman, has a four-paragraph Wikipedia entry with an edit note from 2019, and the little bit of modern writing I could find on the painting focuses only on its depiction of lichen. Still, when my eyes grazed across the crowded wall, I felt my internal shutters tighten and zoom, my heart swelling for this tiny man I’d never met and who, quite likely, never existed.

It was my first time having what museum scholars call a “numinous” encounter with art — one that feels transcendent, yet disconnected from conscious understandings of historical or aesthetic value. In Latin, numen can mean both “a nod of the head” and “divine will”: it’s the feeling of art, or perhaps God, offering silent approval for an act of attention. It’s a type of holiness that seems to sneak up on the viewer, an exchange across the centuries that defies logic.

That’s what I’m after when I enter a space where art (particularly paintings; my brain has yet to digest anything past cubism) is displayed — that unexpected opening of possibility, that reminder that beauty matters, that cosmic pat on the head from the big man upstairs. The numinous is probably not meant to be hacked or streamlined, but as a microplastic-poisoned modern woman, I have spent the years since my monk encounter figuring out how to increase my chances of experiencing it. The result is my (patent-pending, borderline-obsessive) Solo Museum Routine:

It starts with making a big, hasty loop of any given gallery, taking note of which pieces look immediately interesting. A very stylish woman once told me that her secret to secondhand shopping was to move through the thrift store as quickly as possible, grabbing only the items that jumped out immediately — “if I don’t love it on the rack, I won’t touch it in my closet!,” she said. I apply the same logic to artwork — the ones that have something to say to me tend to announce themselves quickly, and I use the first loop to make note of their calls. Sometimes, I take a moment to pose a question I’m struggling with — like a tarot card reading — and ask myself if anything I’ve seen seems to contain some hint of an answer. Then the second, slower round. This gets me properly acquainted with the standout pieces, and I spend a few minutes in front of each. Sometimes I make a third loop, switching direction, seeing if anything else jumps out in context. And then I try to spend 3+ minutes in front of a single piece: my wimpy imitation of the Peter Clothier “one hour/one painting” exercise. This whole routine reframes the museum trip as an exercise in attention and personal aesthetic discernment rather than rote staring, and pushes me away from the completionist tics that make it feel like homework. It also makes me look like an absolute nutcase, and is the reason I’ve never had a successful museum date.1

I arrived at the entrance to “Dangerously Modern” and showed my QR code to a blue-haired woman with intimidating eyeliner. The walls were blue, too. Small groups of women — white hair, soft voices and buttery satin — clustered around the introductory text, which described the group of female Australian artists who picked up their lives to study in the salons of Paris and London at the turn of the 20th century. The show would follow them from these early, isolated periods through their debuts in the European art markets, where their gender and national outsider status established them as an unexpected vanguard in modernist painting. I read under my breath to keep myself focused. Lots of mentions of cold ocean voyages and uncertain futures wagered on vague talent. Did I deserve to relate to them? I don’t know, but my face went hot and my cheeks were wet before I could stop it. “They were so brave,” I murmured. I backed out of the crowd and commenced The Routine.

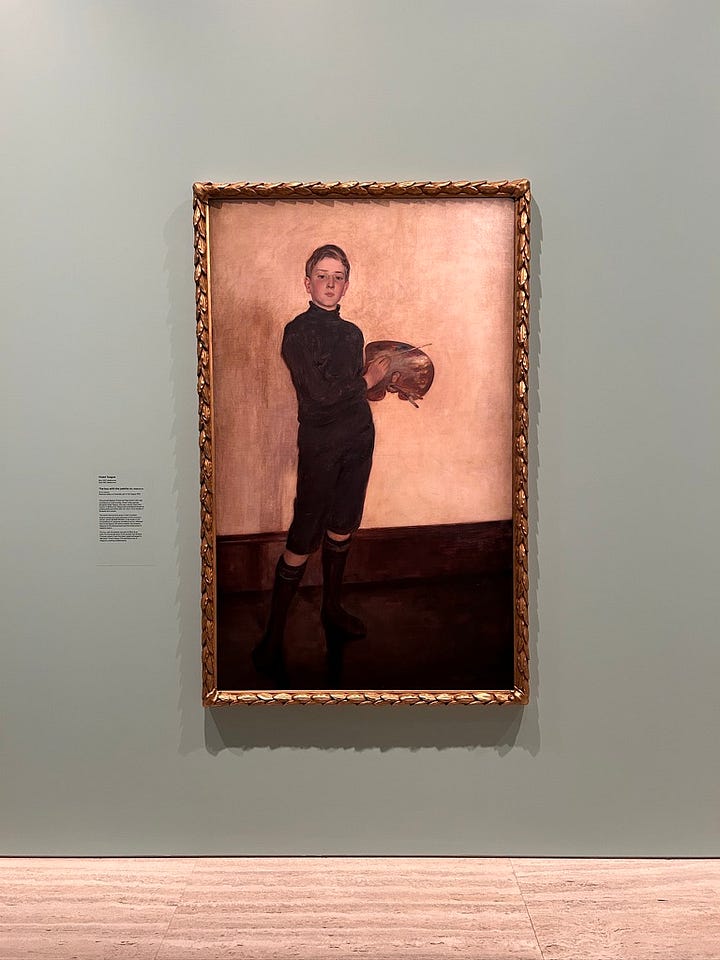

The first piece that jumped out in lap one was a portrait of a rosy-cheeked boy with a paint pallet — cleverly titled “The boy with the paint pallet” — by Violet Teague. It didn’t merit a full “meditating monk” reaction (few things do), but it got me to pause, stepping forward and back hypnotically. The kid looked confident and cocky; several minutes passed before I realized he’d grabbed me. I love this first moment of softening — when the brain clicks over from doing to feeling. My phone, slowly dying, felt lighter; my breathing eased. The Routine was working, clearly, and my view seemed to widen and brighten just slightly: my problems still existed, but I was there. It was special. I’d try to make the most of it.

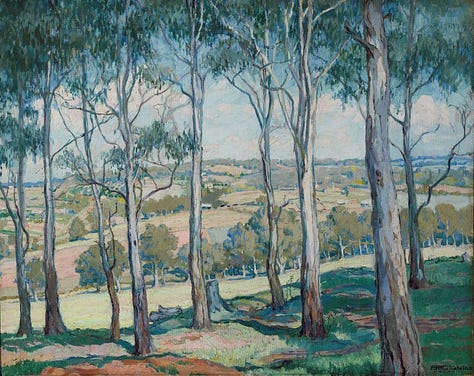

The galleries were roughly chronological, the walls moving from a late-Victorian royal blue to steely gray and early-modern gold. As I walked through, making my busy little loops of each room, my eyes kept catching on the works of Hilda Rix Nicholas, who gained international acclaim for her blobby, boisterous depictions of North Africa, which she first visited in 1912. These paintings are abstract and proudly post-impressionist, using fat, confident brushstrokes in a limited color range to emphasize the unique play of light and shadow on the white-walled markets of Tangier. They seem to be the work of an early, unselfconscious enthusiast, and Rix Nicholas’ letters from the time sound like a woman infatuated: “Picture me in this market-place – I spend nearly every day there for it fascinates me completely…oh the sun is shining I must out to work.”

These early Rix Nicholas paintings hung in a yellow-and-white striped room alongside other paintings of early-20th-century travel and leisure — it looked like a candy store, with bright music piping gently through the sound system. It all seemed a bit too joyful, as if the curators were preparing their audience for a crash. And sure enough, the next room revealed that Rix Nicholas’ early period of inspiration was cut short by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The gallery walls turned a sickening split-pea green; the circuses and seascapes were replaced by widows and searchlights. Accompanying text explained that the heat of war made any kind of “art for art’s sake” seem overly trite; just as Rix Nicholas and her peers were finding early audiences, their work was forced to become more political and pointed.

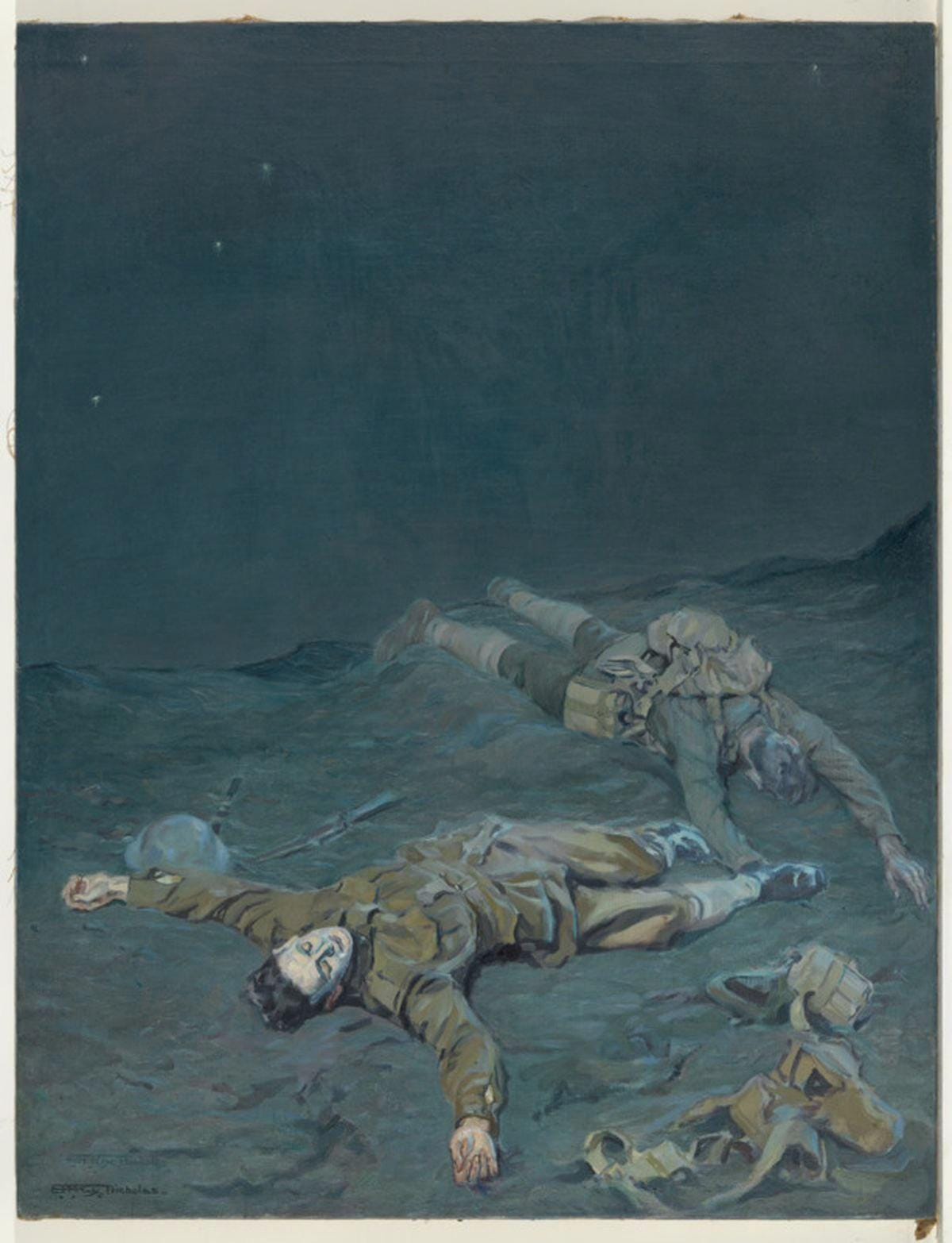

Her painting that truly gutted me was from this period: a 1917 landscape with a grubby, tipped horizon, two soldiers’ bodies strewn in the foreground. The wall text revealed that the main soldier, lying face-up in a cross position, was painted with her husband’s face.

He’d died just a month after they were married, fighting for the British. My breath caught and I stood numb. I often wonder what it feels like for visual artists to stay with the same image or sculpture for days or weeks; staring, tweaking, staring again. Inserting a dead man’s face into that process feels like a unique form of torture, but Rix Nicholas seemed to frame this as a service. Later, she said she wanted to turn her husband’s death into a lesson about the universal toll of war. I imagined her gritting her teeth in front of the canvas in stockings and bloomers, framing her art as a moral obligation. A list of the current world’s horrors ticked through my head; it’s laughable to imagine them being stopped, or even slowed, by a painting. Every artist thinks they’re changing the world, but the machine of power and capital rolls forward ever faster. But she tried. That had to mean something. I sat for a moment and wiped my eyes.

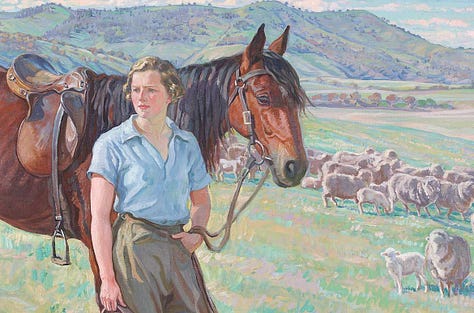

In the next gallery, I learned that after the war, the widowed Hilda Rix Nicholas returned to Australia and moved in with her friend Dorothy Richmond. There, her career lost focus. She tried to paint southern Australia as she’d painted Morocco, depicting it as a kind of Eden, untouched by the war that had sent her life into a tailspin. These paintings were often criticized as overly masculine and simplistic, and they lack the vibrance and specificity of her earlier work. Her push toward message-driven paintings — which seemed urgent in her war period — also curdled into a maudlin sense of nationalism. She returned to Europe in 1924, taking Richmond with her, and selling highly stylized depictions of her nation’s rugged, idealized self-image. Works like “In Australia,” a portrait of a rancher pinching a pipe between his teeth, have a definite Norman Rockwell-meets-Thomas Kinkade quality — they were received well at the time, but seem uninspired and flat in comparison to her earlier pieces, more commercial products than artworks. Something — whether it was the needs of the market or the fist-clenching desire to make a statement — had drained the life from Rix Nicholas’ work.

This period was hardly represented in the galleries; the curators seemed to sense its relative blandness. The one piece that was included from Rix Nicholas’ return to Europe was an exception to her nationalist project: a portrait of her friend, posing in a Paris flat, titled “Une Australienne.”

It’s the kind of painting that’s easy to adore: a flapper-coded Dorothy Richmond tilts her head in what seems like flirtation, showing off her fur-lined coat and salmon scarf. Finally, this gave me the full “meditating monk” reaction. I felt a vortex drawing me toward the painting; a tiny nod from whatever god watches over New South Wales. In the painting, Richmond’s face, slightly wrinkled, looks warm and self-assured; the kind of woman I’d ask for life advice and immediately believe. She’s playing into an archetype for Rix Nicholas’ nationalist project — the self-directed Australian woman as a foil to European high society ladies — but something about this piece escapes the trap. Rix Nicholas’ habit of placing her loved ones in her paintings seemed like self-flagellation when she was grieving. Here, it seems to be an act of joy. Richmond is clearly rendered by someone who cared for and understood her deeply. This piece doesn’t carry the weight of obligation, unlike others from that period. That’s why it persists — and, I think, why it called to me so clearly.

I didn’t stand in front of “Une Australienne” for very long. When I stopped to glance at my phone (now at 18%), I realized I needed to get back to the airport. I tore my gaze away from Richmond — she didn’t want to let me go — and made a final loop around the whole exhibit. I sniffed three gift-shop candles before buying a postcard of the painting and heading back into the overbright courtyard. The children were still chattering in their strollers, and the birds still grimacing.

I was still lost, mostly, and remain so. But as I stumbled through a train station, three incorrect bus halls, and Qantas check-in, I felt a small bit of clarity — not about my artistic future, but at least my (honestly, quite frustrating) insistence on continuing toward it. I bought a chicken salad sandwich and a $19 charging cord in the food court, pulled out my tiny version of “Une Australienne,” and stared at it a while longer.

Art can’t promise change. It can’t promise outward success, either. When it pushes for either of those things, everyone notices. The work curdles. The only thing that art can truly, reliably transmit is attention — which some may call love — across time and space. Under Richmond’s gaze, that transmission didn’t feel like a consolation prize. It felt like the whole point.

The plane boarded earlier than expected, and I fell asleep before dinner service started. The cabin lights were out when I woke up, midway across the Pacific. I half-watched a few scenes of Sinners over someone’s shoulder, then pulled out my phone to start writing. Unfortunately, it’s all I can do.

I actually did have a (semi?-) successful museum date a few weeks after this, but it was in a gallery I’d already seen, so the theory is still untested. I also ran into my therapist in front of a Monet.

What a privilege to get a peek inside your brain. Creating a museum process? Inspired. Never crossed my mind yet I looked at each painting you shared with new eyes. Get working on that patent

the nod, the flapper, undeniably visceral