The first time my heart got broken was when my high school boyfriend moved to college. The second time was when I committed accidental joke theft.

Some background: I was very into Twitter as a teenager. As the cursed combination of theater kid and honor roll student, I had limited options to climb up the irl social ladder. Things felt easier in an online, text-based arena, and I was good enough at wordplay and meme formats to get a sliver of attention from my peers. I fired off quips and jokes with increasing, manic velocity. I was proud of my Twitter account. Weirdly, that didn’t sound embarrassing at the time! Blame it on the hothouse feeling of the adolescent social web — or just my own adolescence.

Anyway — as the little bird app took up more and more of my brain-space, I developed complex, silly workflows to optimize my output. I had a note with half-ideas or concepts I wanted to play with and a drafts folder five thumb-scrolls long. I used the like button (psychotically) as a bookmarking tool for phrases and formats to riff on, and religiously un-liked anything that didn’t feel relevant or interesting. If I unintentionally offended you by un-liking your promposal pictures in 2014, I apologize, but I was on a mission. I was going to have the best high school Twitter account in Thurston County. It was life or death! And, like any good content strategist, I needed to scope out the competition. So, sometime around the fall of my senior year (weeks after the boyfriend moved to Seattle, for those keeping track), I added another step. After drafting up a tweet about Drake’s little Hotline Bling dance or the Hamilton soundtrack or whatever we were talking about in 2015, I searched what else had been said about it on the site.

And that’s when my world crumbled. I realized that other people were noticing the same things. I realized that some of my tweets — the punny, low-effort ones — were exactly the same as other people’s.

Of course, as an adult, I can see that this was to be expected. There are only so many notable things in a suburban teenager’s existence, and there were more than 300 million users on Twitter at the time. Maybe if I hadn’t dropped my statistics class, I would’ve understood just how normal this experience was.

I was crushed anyway. I saw it as a failure, and I worried that I’d subconsciously stolen the jokes. I worried I’d cheated my way into other people’s digital good graces. My Twitter use slowed down after that.

It was definitely an overreaction, and looking back, was probably for the better. If I kept going at that pace, I’d probably be a furry or a libertarian by now. Still, that moment sticks with me. I think all of us have had a revelation like it — when we realized, thanks to the internet, that our beautiful-precocious-original minds weren’t as beautiful, precocious and/or original as we once thought. Hell, you’ve probably had a moment like that today. Think of the TikTok comment that felt like it came out of your own mouth, or the viral essay that perfectly mirrored a conversation you had a few nights ago.

It’s a common experience, but a destabilizing one. On a bad day, even in my grown-up brain, these groupthink moments can feel like defeat. They’re a depressing reminder of the sheer scale of the internet, the millions and millions of metaphorical monkeys banging away at metaphorical keyboards. They can create an overwhelming feeling that everything worth saying has already been said, and everything worth doing has already been done.

Recently, there have been a slew of articles about how “no one’s talking on the internet any more.” The writers make some good points: that group chats feel safer, that TikTok and its clones are more suited to selling than actual connection, and that power-users and mods have (rightfully) gotten tired of creating value for platforms that don’t care about them and withdrawn their labor as a result. But there’s another element that I think has been overlooked — the push to be original online, and the paralysis that accompanies it.

See, no one seems to know what to do in digital spaces at this point. As Ian Bogost wrote in The Atlantic, we’re caught between the age of social networking — interacting online as we would in real life — and social media — treating our feeds like one-person production companies. Here’s how Bogost illustrates this shift:

Instead of connection—forging latent ties to people and organizations we would mostly ignore—social media offered platforms through which people could publish content as widely as possible, well beyond their networks of immediate contacts. Social media turned you, me, and everyone into broadcasters (if aspirational ones).

I think over the last few years, many of us have realized that broadcasting is fucking exhausting. Layering the standards of commercial media (timeliness, hookiness, brand cohesion, a “niche”) on top of our social lives is an obvious recipe for disaster. And when we apply those standards to our creative lives — well, that’s how we end up searching our own jokes on Twitter. That’s how we stop creating anything at all, for fear that it’s already been done.

I say “we” here, but I’m just talking about myself. I’ve wanted to post my writing on the internet for a long time. I’ve been a professional writer ever since I graduated college, but my words have always been hidden behind some larger editorial brand or, quite literally, put into someone else’s mouth. I didn’t have a problem with this, but as the years went on, the desire to create something for myself, as myself, buzzed around me like a persistent mosquito. Dozens of half-formed ideas for podcasts and video essays and op-eds popped into my head, and I dutifully entered them into my notes app, dreaming of the day that I’d deliver them as polished, perfect little jewels.

But then I made that mistake again — I compared them to the entire rest of the internet. Unsurprisingly, none of them seemed interesting enough, marketable enough, or unique enough. So I gave up. They didn’t get made, and I didn’t get better.

I was stuck in this cycle for years, but something shifted in the last few months. Blame it on losing my big fancy writing job or on a quarter-life crisis or on tattooing that one Ira Glass quote to the inside of my eyeballs. I became so, so tired of being scared and stuck. I realized that I needed to allow my work to be messy, imperfect and (maybe) a little bit generic in order to improve. So, that’s the goal of this newsletter: a place to play and tinker, to probably suck (at first!) and maybe improve (eventually!). To reject the publisher mentality and do my best to create something just because it feels good.

Of course, it’s an odd time to be writing about originality, especially as it relates to the written word. The idea of trying to get “ahead” by saying something never said before feels increasingly idiotic these days, as generative AI tools grow in capability and ubiquity.

AI keeps me up at night thinking about my dwindling job prospects, but in a strange way, its ascendance has emboldened me to put my shitty, early-stage work out there. It’s hard to be so precious about things when it feels like the world is ending, and I’ve found it easier to accept that a piece of writing doesn’t need to be groundbreaking or perfectly-crafted to deserve a place in other people’s hearts.

I read a lot of commentary about the possible effects of AI on the writing profession in the past few weeks — I’ll link a few below. While none of the pieces offered the clean “it’s all going to be fine” narrative I was really looking for, I found Vauhini Vara’s essay in WIRED to be the most measured and thought-provoking. I highly recommend reading the whole thing, but she ends on a slightly hopeful note:

I have no doubt that AI will become more powerful in the coming decades — and, along with it, the people and institutions funding its development. In the meantime, writers will still be here, searching for the words to describe what it felt like to be human through it all.

It reminded me that there is something noble about struggling to put thoughts into words and pen to paper, even if an algorithm can do it more efficiently. The inherently competitive structure of social platforms has already devalued all creative work, making its market value so obvious that its spiritual or connective value is almost entirely eclipsed. It pushes us to think of our work only as a product, rather than an artifact of thought and feeling.

AI tools will likely get better and better at the productive part of the equation, but the thought and feeling part? That’s all us. We need to be careful not to give it away too easily.

Put in this context, the jokes that I accidentally parroted weren’t evidence of a shameful lack of originality. They were evidence of a shared experience. It’s kind of delightful to think of multiple brains, separated by time and space, thinking the same silly thought. Moving forward, I’m trying to frame online synchronicity not as a threat to my content strategy, but as an invitation for connection.

The keyword there is try. Honestly, I can only access that kumbaya, Julia Cameron-coded headspace every so often. I am still terrified of being unoriginal and uninteresting, of wasting readers’ time. There’s one more sentence in the Vara essay that I didn’t include above. After singing the praises of the messy, slow-moving products of human writers, Vara asks: “Will we read them?”

I’m putting that question to the side for now, at least as it relates to my own work. It haunts me nonetheless, and pushes me to continue supporting my favorite writers and artists with attention, time and money wherever I can.

I titled this newsletter “Acme Thought Corp” as a little joke to myself. If I’m going to be generic (which, as a beginner, I kind of have to be), I might as well embrace it, right? But as I thought about it more (and watched a lot of cartoons), the meaning grew more complex.

Based on its appearances in the Coyote vs. Road Runner animated shorts, I assumed that Acme was an early-20th century version of a Kirkland Signature or Up&Up: a bland, all-encompassing brand that seemed to make one of everything. And I’m not the only one.

According to this unnecessarily sassy Wikipedia entry, the name has “been falsely claimed to be an acronym” for “A Company Making Everything,” and “American Company that Manufactures Everything.” But it was never a single entity.

According to Warner Brothers animator Chuck Jones, it started as more of an inside joke: at the time, hundreds of independent businesses called themselves “Acme” in order to be listed in the first few pages of the phonebook. Seeing them all lined up next to each other — “Acme Autobody,” “Acme Cleaners,” “Acme Drugstore” made it look like they were all subsidiaries of one massive company.

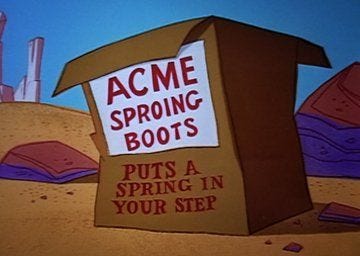

The word itself is Greek in origin, meaning summit or peak, so it was funny to imagine a gigantic conglomerate spread so thin that it tried to make everything — and I mean everything — imaginable. We’re talking earthquake starters. Roller skis. “Sproing boots.”

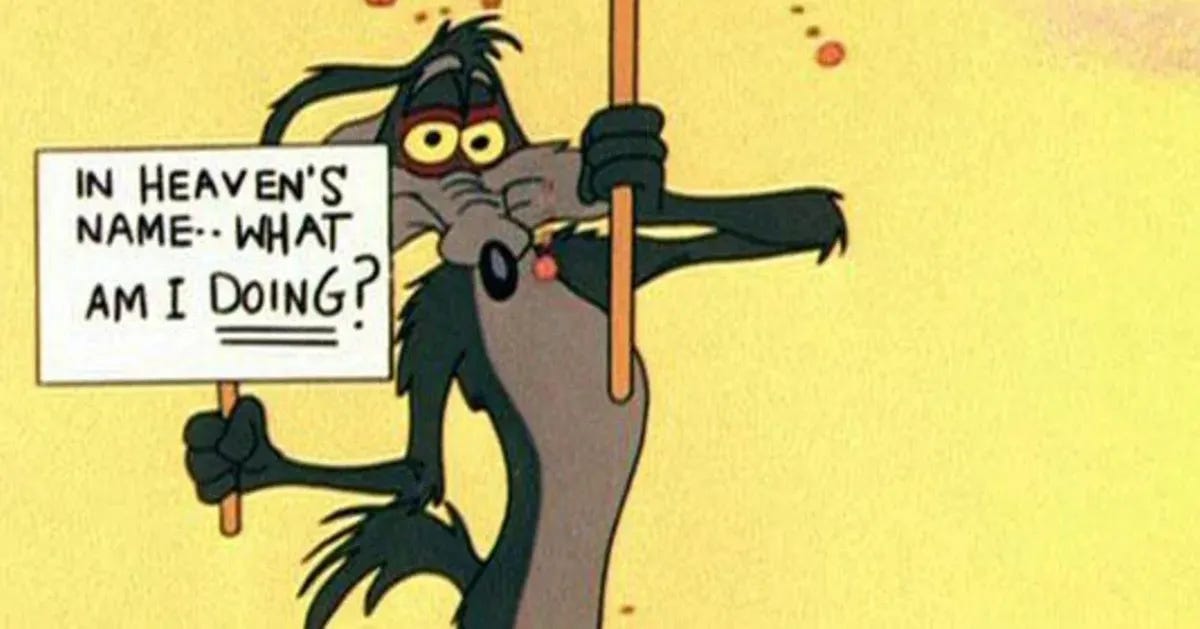

None of these products work, of course, and most of them actively backfire on the coyote. But, weirdly, that doesn’t stop him from ordering from them again. They’re the only tools he has to get closer to his (impossible) goal of catching the road runner. If you’ll allow me an out-there analogy, the Acme products are kind of like language in that way: simultaneously cookie-cutter and inventive, remarkably capable and inevitably prone to fail. Luckily, words don’t literally blow up in our faces, Wile E. Coyote-style, in the pursuit of our personal road runners. That doesn’t stop it from feeling like they can.

This newsletter is mostly an exercise in facing my fears, so I’m keeping the stakes low and simple: write consistently and hit “publish” consistently. My goal is to put something out every two or three weeks, but again, I’m being gentle here. I know that I love essays, criticism, and nonfiction writing, and that I want an excuse to think and read deeply about the things that matter to me. I know that I will never improve unless I accept the possibility of publishing work that could be seen as underbaked, under-researched, self-indulgent, derivative, or all of the above by myself or others. I’m deciding to smack into the painted-over rock face, light the absurdly long TNT fuse, and strap on the Acme-brand sproing boots anyway.

I want to run off the cartoon cliff and turn my head to the camera, giving a little shrug while my legs fall to the desert floor, my head remaining in the same place just long enough to jot something down.

I know I will never catch the road runner, but I’m teaching myself to love the chase.

Thanks for reading. My future essays probably won’t be this long, this meandering, or this self-involved — but if they are, that’s okay! I appreciate you being here. Now, here’s a 6 minute video of Acme products backfiring on Wile E. Coyote, and a list of my sources/inspirations for this essay.

further reading

Confessions of a Viral AI Writer, Vauhini Vara, WIRED

Road Runner (all episodes), Internet Archive

Catch Me If You Can! Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner, Havahart.com (I think this is the blog for a pest control company? But they slayed here, no pun intended)

Wile E. Coyote and Capitalism: ACME and the Profitable Pursuit of Desire, Jon Holmes, Movieweb

We’re All Living in r/MadeMeSmile’s Internet Now, Ryan Broderick, Garbage Day

We’re All Lurkers Now, Kate Lindsay, Embedded

The AI Detection Arms Race Is On—and College Students Are Building the Weapons, Christopher Beam, WIRED

Ghosts, Vauhini Vara, The Believer