may and I do not get along

notes app strays ft. elena ferrante, family secrets and the caves of altamira

Things tend to get weird for me in May, and this year was no different. I’m pulling a Knausgaard in an attempt to tease it out. Some of these are true and some just sound good, and they’re out of order in some attempt at a narrative arc.

It’s more acidic than what I’d usually allow myself to publish, but irrationality and emotion are the things that separate us from the machines, so. We’re trying it.

I.

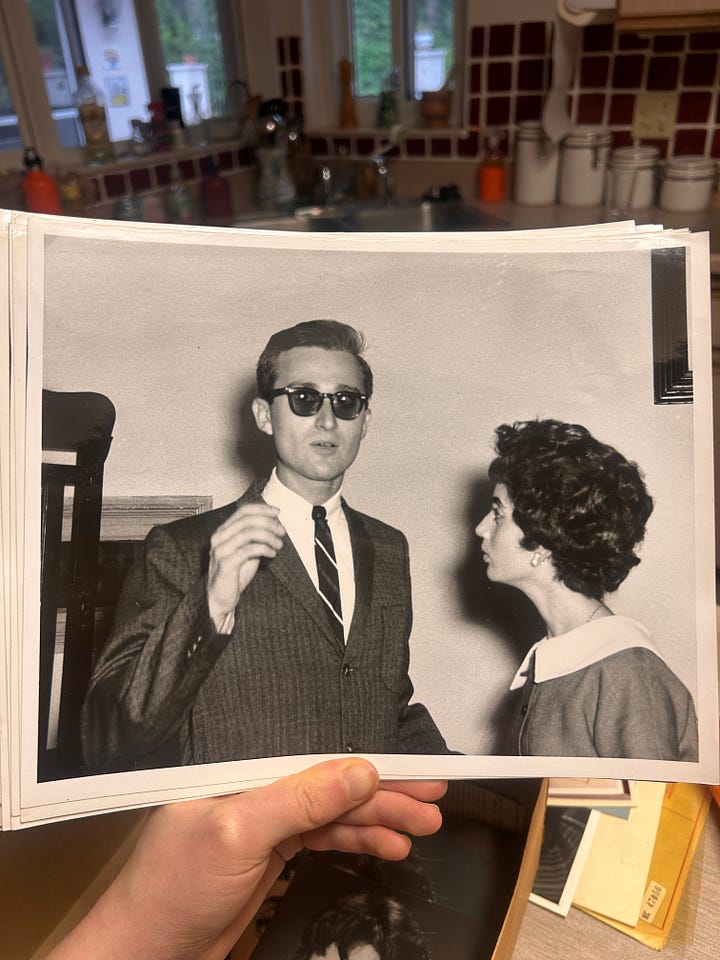

I spent a surprising amount of time with my grandparents’ wedding photos this month.

They passed away a while ago — my grandfather in the fall, my grandmother in 2022 — so the grief had time to subside. The stuff, however, would not go away on its own. The family spent three days sorting, stacking and labeling the items we wanted to keep, before the estate sale brokers swept through. It was overwhelming, really, the layers of history in that house, and I got pulled down multiple rabbit holes of family lore. We learned my great-grandfather made a spoken-word LP that loosely translates to “Paths of Happiness”; we found a printed-out copy of the Loma Linda cleanse circa 1976, we found photos of my grandmother at a topless Spanish beach. The two of them lived a long and slightly-glamorous life, so there was a lot to dig into.

For context, my grandparents have the kind of star-crossed love story that makes bile rise in the stomach of the modern dater. He was an American stationed in Havana in the late 1950s, and, as the story goes, saw my grandmother walking down the street with ballet shoes dangling from her fingers. She was 19, a dancer, tiny and luminous. Her deep-set, hooded eyes looked like a Spanish Bette Davis. Their courtship has a bit of a mythical quality to it — my grandmother’s family, the Saínz de la Peñas, had access to an upper-class Cuban milieu. My great-grandfather’s position writing for the newspaper’s society pages certainly helped with that, and might have also helped the young couple secure tables at the Tropicana and the Casino de Capri. When we were cleaning out the bedroom, we found a handful of cocktail stirrers from these clubs — the thick, garish ‘50s plastic pressed into shapes of dancers, palm trees and flamingoes.

They married on July 4, 1959, in a glowing white cathedral. Fidel Castro had become Prime Minister about five months earlier. While I’m still trying to understand the full timeline of the revolution, I think it’s fair to say that by this point, they knew the country was on the brink of upheaval. They knew that their particular brand of Cuban life was swiftly disappearing. Within three years of that wedding, they were in the United States permanently, never to return. The idea of their (relatively brief) time together in Havana took on a totemic quality, and the story of their early relationship was told so often that I hardly took the time to interrogate the visceral, emotional reality behind it. It was only when I was confronted with those pictures — pounds of pictures — that I started to wonder how this transition actually felt, and attempted, feebly, to compare their young adulthoods to my own.

I was slightly disappointed to find no journals, annotated books or personal writings from either of them — hardly any documents of their individual inner lives. There were love notes, which my braver cousins read with slightly widened eyes, but I was too much of a prude to read them. The two of them were in the house as a kind of negative image, living in the space between this constellation of objects — the CDs, the magazines, the Burberry coats. It’s the complete opposite of what I would leave behind if, heaven forbid, someone was forced to divvy up my stuff: twelve journals and a pen collection and 500 ideas left unfinished. But they were from a quieter generation, graceful to the point of impenetrability. Being a dancer, my grandmother was able to find peace in wordlessness — a skill that I, obviously, have refused to learn. Some kind of Rosetta Stone to their inner lives would be against character. Instead, we got countless artifacts of the love between them and the life they managed to build. That offered a kind of clarity in itself.

II.

Had a 48-hour period where one man said he didn’t love me and another sent me into full-on fight or flight (maybe the good kind) with half a second of eye contact. It’s okay for me to publish this because one of them doesn’t know my full name and the other (I suspect) can’t read. Guess which is which.

III.

I yanked My Brilliant Friend off the shelf before leaving for the airport. I tried to read it a few years ago, but bailed around page 200. My cerebral cortex is fully formed now, so it’s going much better. Something just feels right about reading about midcentury Italian tweens while shuffling through reams of black-and-white photos, and the clay-toned house in Flagler County always felt distinctly Mediterranean to me.

As the first novel of the Neapolitan Quartet, the book follows the first sixteen years of a contentious, lifelong friendship between Elena Greco and Raffaella Cerullo, both born in 1944 in Naples. Narrated by a middle-aged Elena in an extended flashback, it has a relentless, churning quality, ticking through major life events in both of the girls’ lives as they move toward womanhood. Their paths slowly diverge as Elena stays in school and Raffaella (called Lila) moves toward becoming a housewife.

Elena is a relatable narrator — painfully so — for any woman who has felt she is doing womanhood wrong, which might be all of us. Even throughout the first book (and I’m only midway through the second as I’m writing this, so don’t spoil anything), she constantly seems to be fighting the gravity of her gender and all the cruelty that comes with it. She’s clearly smart and ambitious, but refuses to see the good in herself, and uses Lila as a universal object of comparison: more beautiful and brave than she, more desired, more effortless and deserving. Midway through high school, she notes that Lila could even check out library books better than she could: “It occurred to me that if Lila had taken out just a single book a year, on that book she would have left her imprint and the teacher would have felt it the moment she returned it, while I left no mark.” Oof, girl. Been there.

More than anything, I want Elena to win. I want her to stay in school, move to Rome and find some fantastic career for herself. But the wins don’t come easily. Instead, I’m given a first-row seat as self-doubt swallows her whole.

I found myself crying in an offhand moment when she receives a shower of compliments for a paper on Dido, the first queen of Carthage as depicted in the Aeneid. Her main thesis has something to do with the collective emotional state of cities — the way that love can be baked into streets, and the evil that can emerge when that love disappears. This idea first showed up in an offhand conversation with Lila several months earlier, but Elena gave it form.

Her teachers are floored; they pass it around and pull her aside, truly impressed by her writing abilities. It’s an exciting moment of recognition for her as a student and a writer. As I read it, all I wanted was for her to own this accomplishment, to follow this flicker of talent to the ends of the earth.

But immediately, she undercuts herself: “the fact that…I was a student with a reputation for being clever soon seemed to me unimportant. In the end what did it prove? It proved how fruitful it had been to study with Lila.” Brutal. She moves on from the essay quickly, insisting her teachers’ praise means nothing.

I remembered a loop of handwriting that a professor left on one of my papers in freshman year of college, asking why I wasn’t pursuing an English major. I never answered; I was convinced I wasn’t smart enough. Looking back, I want to bop 19-year-old Kylie over the head for that, just like I want to bop (much more gently) 14-year-old Elena. I want to make her — them? me? — realize that those clear moments of recognition do not come along often. As I’m writing this, I’m worried that she, too, will not act upon it for the sake of what’s safe and customary — that she’ll be forced, in short, to grow up.

IV.

I’m in this dangerous post-Eurovision period where my musical taste has been so profoundly fucked that I think this Finnish (?) italo-disco song about the Monaco Grand Prix is the only honest piece of music ever put on this earth. I need to go on the musical equivalent of the BRAT diet (that’s banana, rice, applesauce, toast — nothing to do with Kamala or Ms. XCX) to even myself out. Only ambient drones and light techno for the next two weeks. My Instagram Reels algorithm also took a dangerous turn toward horny Eurovision edits, so I deleted the app and threw my phone across the room. I can’t go down that path again.

Also yeah, I only wrote about half of the entries this year, because I ran out of time and was cleaning our my dead grandparents’ house. Forgive me.

V.

Every two weeks or so, my brain latches on to a song and demands that I play it 8-12 times a day until I’m sick of it. Most recently, it’s been “The Caves of Altamira” by Steely Dan. Something about contrast between the image depicted in the lyrics — a melancholy guy having his shit rocked by ancient Spanish cave paintings — and the shimmery, aggressively 70s horns just does it for me. Cave paintings are definitive proof that humans are uniquely gifted at two things: making art and being sad. This has been the case for, at minimum, 36,000 years. Always worth a reminder.

VI.

Worried that I’m slipping back into my old ways: crying, complaining, eating soup alone. It’s 48 degrees on May 22 and I doubt I’ll ever be warm again. Work went late and the clouds were blue by the time I logged off.

It’s “Fleet Week” — a new concept — and fighter jets roar over my building, shaking the windows. I make things worse for myself by chipping away at a freelance project for an extra hour. It’s a four-day weekend. I have no plans.

I’ve been trying to avoid using the word “loser” so much, because it makes my inner monologue sound like the bully in a PBS Kids show. “Loser” is so perfect, though — I have yet to find a word that captures that same pathetic sense of slackness, that shruggy evocation of non-action and the natural consequences thereof. Someone asks me out on Hinge and I ignore them because my eyes are puffy and my bangs already flat. It’s not rude. I wouldn’t be good company tonight anyway. I had a panic attack in the afternoon — the kind that stops my hands from working and sends my brain 3 inches above where it should be. I laid in bed for an hour, half-checking Slack, and had to wash my face before I could return to the desk. I pulled my headphones too tight, pretending they were one of those acupressure headbands that approximates the womb. I played Aphex Twin at low volume, promising myself that by the end of Selected Ambient Works 85-92 (one hour, fourteen minutes), I would feel better. Feels awful to need scaffolding like this to respond to set up calendar holds. I remind myself that I’ve spoken to three people today, and all of them were through a screen. Okay, problem identified. No idea how to fix it.

I often complain that my life doesn’t seem “real,” and I blame it on working from home, but I know that’s not the whole problem. In my mind, there’s a sense of momentum that would come with going into an office every day, going anywhere every day. But I’m also aware that life in a cubicle would come with its own sense of claustrophobia. I couldn’t have a panic attack at 3 p.m. in an office, and if I did, my coworkers would be forced to see it, and then I would, I don’t know, get fired and go broke and die??

In some corner of my mind, there’s an alternate version of me who commutes somewhere, who works hard because she loves it. She puts on one outfit at the beginning of the day and keeps it on until she comes home from evening plans. Her bangs don’t fall and her time feels, at least nominally, her own. The grooves of social interaction and day-to-day routine remain greased and ready, which keeps her charming and fun enough to make friends easily and not sink into spiky, self-pitying spirals like this one. That life does not seem out of reach, to be honest, and somehow that makes things more frustrating. I worry that I’ve stumbled into a professional dead end that I can’t get out of. I’m scared that as time passes, it becomes less and less likely that I will be able to hit reset and try again. I open new tabs on masters’ programs and pitch calls with the desperation of a pill blister pack, but rarely do anything with any of them.

I envy the people who drifted after college; who allowed themselves to be scared and lost rather than filling their time with the sensible and the mind-numbing. But I do not trust myself to the instability that that kind of creative life seems to require. I’m afraid I’d never be able to sacrifice or handle the stress involved. I am too delicate and need too much. At the same time, I feel like at some point, the leap must happen. Doesn’t need to be soon, necessarily, and might not involve leaving the 9-5 grind. I don’t know. As awful and big-headed as it feels to say, I’m certain that I am good at something, and suspect that with the right amount of cultivation and training, I could be very good at it.

It pains me to imagine a life where I continuously push writing to the margins. The only thing that gives me hope is the knowledge that I cannot accept this kind of pain for long. Something else must be possible. Is this what grad school is for? Don’t answer that.

VII.

An email from an astrology app told me that my Saturn return starts tomorrow. Sick.

VIII.

Ghosted someone because he didn’t know what stand-up comedy was. Like he invited me to a comedy show and when I said “is it stand-up?” he responded with a question mark. When I sent him the Wikipedia page, he said thank you, and seemed to actually mean it.

IX.

It’s 6 p.m., and there’s a baby at the WeWork. I didn’t know they allowed babies in the WeWork. Maybe that means I’m a fake believer in the whole “domestic labor is labor” thing. She’s a recent walker, and paces over the square brown couches in red cotton pants and a Bambi t-shirt.

She’s carrying a paper cup, lifting it to her mouth with two hands and then tapping it on the floor rhythmically. Lift, tip, tap tap tap. Lift, tip, tap tap tap. I don’t know if she’s trying to get my attention or someone else’s. How do I explain a WeWork to a baby? There’s a white stain on her upper lip, the remains of whatever yogurt or milk was in there. Is it breast milk? Would a recent walker still be drinking breast milk? Will I get thrown out of the Financial District WeWork for even typing the words “breast milk?” One World Trade is on the other side of the plate-glass windows. I realize I would’ve seen 9/11 from here, which is a thought I’ve literally never had before. I make a joke about loving to see young female founders, and hate myself for it.

X.

I swear to God that poodle was wearing Crocs.

XI.

Can’t sleep on the plane to Newark. I used to bring an eye mask and neck pillow for every plane trip, but my airplane attire has become progressively slapdash and masochistic over time. Maybe I’ve realized it’s silly to believe that a 31” x 17” pen can ever approximate “comfortable." Maybe I’m finally learning to accept suffering.

I’m currently wearing a sweatshirt baggy enough to earn a “ribcage” patdown (that means they check your underboob) at the Daytona International Airport, and I’m freezing. The hood’s pulled all the way up, AirPod Maxes clamped over the top, like the worst kid in a 10th grade English class. I’m in the window seat, hoping to get a glimpse of something interesting when my plane inevitably goes down. Fog precludes that possibility. There’s just a bruised blanket of clouds and a few stars hanging on marionette strings. I try to sleep.

My neighbor is watching Past Lives, a movie about love and computers. I blink open whenever a bright white screen pops up, which is approximately every ninety seconds. The plot proceeds in stop motion: I watch Greta Lee fizz and giggle in front of a Skype window, chatting with her long-lost crush, Teo Yoo. Three blinks later, she smiles chastely in front of the slightly-lamer man who will actually become her husband. Two after that, she melts when she meets Yoo in real life. The whispery song I’m listening to says that you only think about falling in love and I only think about you. I gnaw on a few of my own maybe-lives like a dog with a bone. Three mornings in a row, I’ve known that I needed to cut someone off because my imagination was outweighing their reality. We are nothing; never have been. It’s the kind of connection you’re not supposed to cry over, the kind of voice you’re not supposed to relax into.

I’m not sure how much a dream weighs, but I know I get sore when I carry too many. Pound of bricks, pound of feathers.

Back to Past Lives; Newark; the airplane. The woman in the middle seat isn’t even watching; she’s slumped in her boyfriend’s lap, earbuds dangling. The movie’s not for her, clearly. It’s for freezing idiots like me — those hung up on people who don’t deserve it, riding the high of something sweet and poisonous. The movie ends almost exactly on time, hitting its final scene as we descend through the cloud cover. The crush’s visit is over, and Lee is slowly accepting that their connection was bound to a specific time and place. She walks him to the sidewalk to catch a taxi. The husband is left standing dumb with his fluffy hair and rumpled shirt. The two of them stand on the cold street. The Wikipedia page describes them exchanging “long, meaningful looks at each other.” They’re just close enough to kiss, and they lean in slightly.

Just then, the movie freezes. The plane starts jumping side to side; clouds flash red and lightning-white. “Rough air” is what they call it now; a euphemism I’ve only recently learned to be afraid of. I fixate on the distance between Lee and Yoo, the invisible presence of The Husband standing between them. I know how the movie ends: sparks fly but nothing catches; Lee returns to her Brooklyn apartment and steady partner. Weirdly conservative in its message, honestly. The anti-All Fours. Maybe correct, for all I know.

The bucking continues, and I try to focus on anything other than the words “radar outage.” This is the kind of disaster that neither a boyfriend nor a beloved job could save me from, I tell myself. I’d die no matter how well I was doing. That calms me, oddly. I slap myself on the wrist; we’re not supposed to be soothed by thoughts like that.

X.

Took a personal day yesterday because my eyes couldn’t stay open and I needed to walk in the rain. I often suspect myself to be a pathologically slow mover, and should know by now that I can’t jump straight into work after traveling. I need a full day of nothing to get my head on straight.

I like the slight sense of foreignness that a few days away can bring to my daily routines. I always end up rewriting my entire to-do list after a trip, telling myself that this planner or notebook or app will be its final resting place. The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn't exist, and his second greatest trick was productivity advice. I have a deep-set suspicion of the calendar app; I am too familiar with the sinking feeling that sets in when those optimistically-placed orange blocks start to crowd and overlap. No amount of emojis and lowercase event titles can diffuse the raw visual proof that I am not as infinite as my best moments convince me.

I had a psychiatrist appointment — one of those box-checky telehealth ordeals that make modern medicine feel like a remarkably boring roleplaying game. Yes, the meds are still working. Yes, I still need them. I’ve been giving these answers for years, and for years they’ve been true. But I’m always struck by how easy it would be to lie. Then, because I’m awful, I ask myself if I’m lying, if I know it, if I’d even know if I was. Some manifestations of the profound world-brain mismatch we call mental illness are obvious — I have experienced those before. The tension between how my mind moves and the expectations set upon me are more subtle now. I try to be grateful for that. “Care” used to mean a set of locked doors. Now it’s just a woman with statement glasses I call once a month. That’s something.

Unprompted, the psychiatrist tells me that I shouldn’t be scared of the future. Hovering behind the scrim of a HIPAA-compliant Zoom call, she says she switched careers at 37. Again, unprompted. “When you’re my age,” she says, “you realize that stuff” — by which she means career and marriage on the five-year-plan — “doesn’t matter.”

I don’t know what specific pheromone compels women in their mid-40s to say things like this to me. I don’t like admitting that my Pigpen-like cloud of anxiety is so visible to the trained eye. I don’t know why I need near-hourly reminders that I am exactly where I need to be, and I don’t know why I can’t believe it.

what do we think of this format? fun? weird? oversharing? bad? I genuinely don’t know how I feel about it, but wanted to play around with form a bit and maybe provide some solace to people who are in a similar state of Lost. I’ll be okay, you’ll be okay, and PLEASE don’t accuse me of autofiction! as always thank you <3

so many gorgeous lines in this - thank you!

maybe it’s time for me to try steely dan