This was supposed to be a New Year’s essay. More specifically, this was supposed to be one of those cute little in and out lists that were going around a couple weeks ago.

I was going to talk about the fresh feeling of January 1, how it complements and exacerbates my tendencies toward 1) outrageous goal-setting, 2) spiraling about the future and 3) harebrained, vibes-based cultural analysis. I might’ve even said it was my favorite holiday – not because I love Party City streamers or drunk Andy Cohen, but because it puts everyone on the same page emotionally, serving up an uncomfortable (yet thrilling?) mix of introspection and hope.

I was going to talk about how social media is best right before New Year’s, because everyone’s brains are rotting in the same direction. Users are just bored enough to remember their mistakes, and just energetic enough to consider fixing them. It’s a hopeful, quiet, germinating time. I love it for that.

Then, I was going to tie it up with some cute little blurbs about the trends I saw on the horizon (the big hitters were Victoriana, blatant male thottery, maybe World War III?), and the things I planned to leave in 2023 (introversion as excuse, projecting motives, stage fright, video essays).

It was supposed to be fun. I tried to treat it lightly. But I got stuck trying to figure out *why* social media users seemed to be so attracted to this format, this year, and seemed to be rejecting more traditional New Year’s resolutions in its favor. I tried to pin down my feelings on goal- and resolution-setting, which felt aggressively meta because my aspirations for 2024 mostly revolved around writing and publishing without driving myself insane. Spoiler: I did drive myself insane. The usual cast of characters arrived: perfectionism, nihilism, unworthiness, and January came and went without publishing anything at all. The original news hook faded into the rear view. And now we’ve landed in February, where dreams go to die.

I feel like I need to add a disclaimer here that I know New Year’s resolutions are kind of stupid. Still, I drink the Kool-Aid every year, for better or for worse. In January, I feel invincible and excited for the year to come. In February, the shine wears off. I begin to feel shaky and uncertain.

If January is the brief pause at the top of the roller coaster, then February is when the cars begin to tip, my stomach rises into my throat, and I realize I’m not as in control as I thought. There’s some kind of set track, but I can’t see where it’s going.

I guess I’m just describing Space Mountain here. Fuck. It’s the end of February. I’m stuck on Space Mountain. Maybe you are too. Maybe you also need a check-in on those intentions set a couple weeks ago. Maybe I’m just pissed off at this chunk of writing and want an excuse to stop looking at it. Whatever. Here’s my resolutions essay, eight weeks late.

I’ll start this off by saying that I’ve always struggled with finding the line between self-betterment and self-punishment, which makes me the target customer for things like grad school applications, eating disorders and New Year’s resolutions. Something in me really gets off on dreaming up gigantic, borderline impossible goals and convincing myself they’re fully within my power.

I fall into a common cycle with these goals: hitting all the marks in January, starting to stumble in February, actively avoiding in March, and trying to forget they ever existed by mid-April. Some years, I’ve tried to dodge it by not setting goals at all, but then I just feel rootless. Turns out I am a hopeless Gregorian calendar stan. So, recently, I’ve tried to not rebuke these self-betterment tendencies, but instead find gentler and more holistic outlets for them. Intentions felt too wishy-washy, and manifestations just made me self-conscious. This year, an answer came via the FYP.

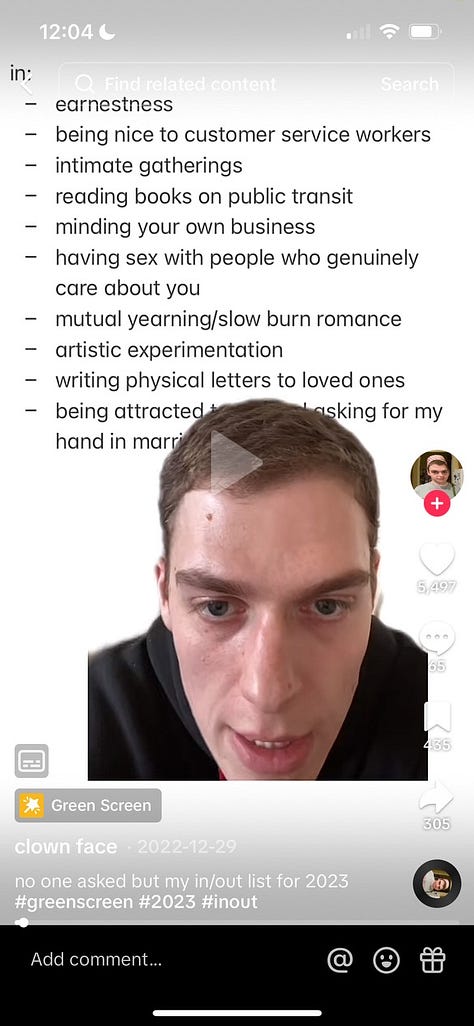

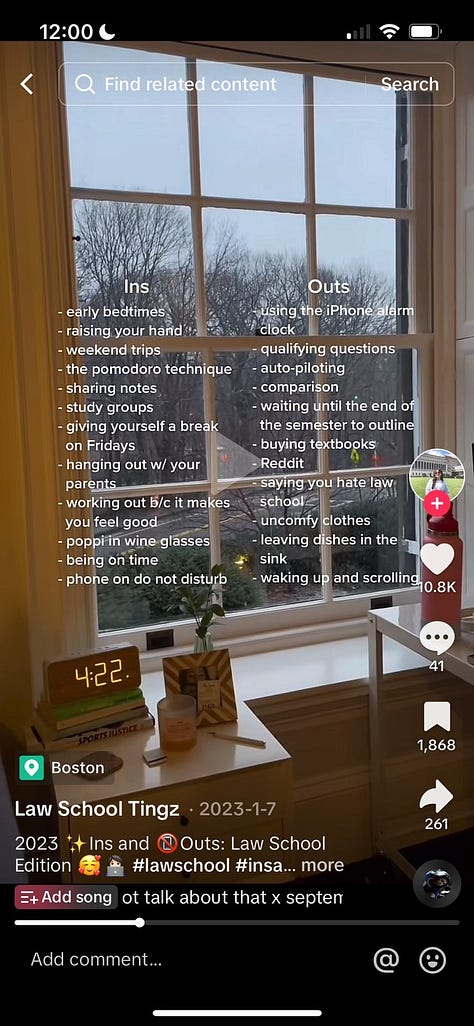

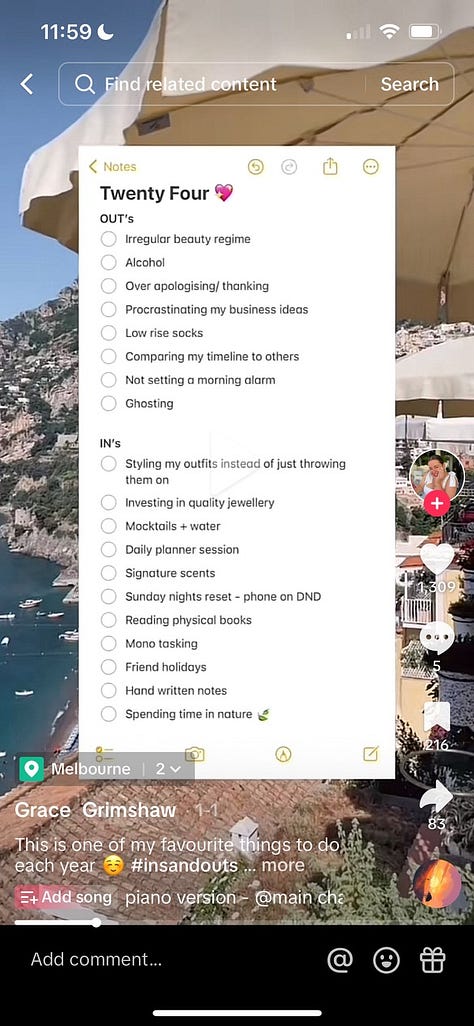

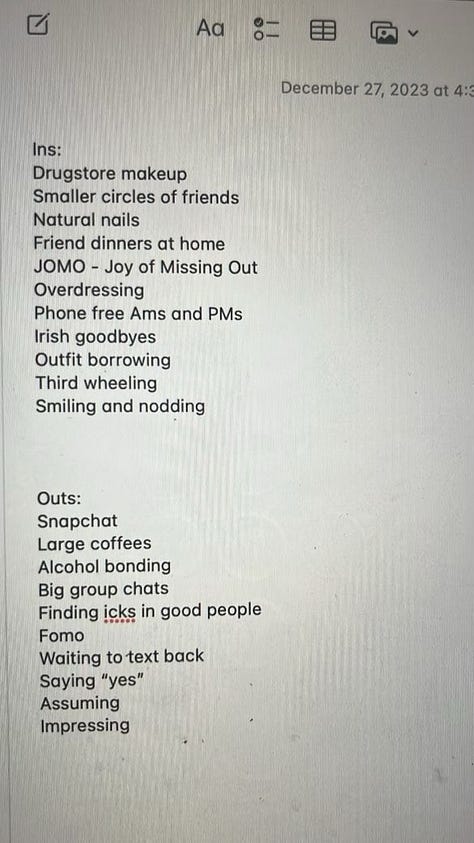

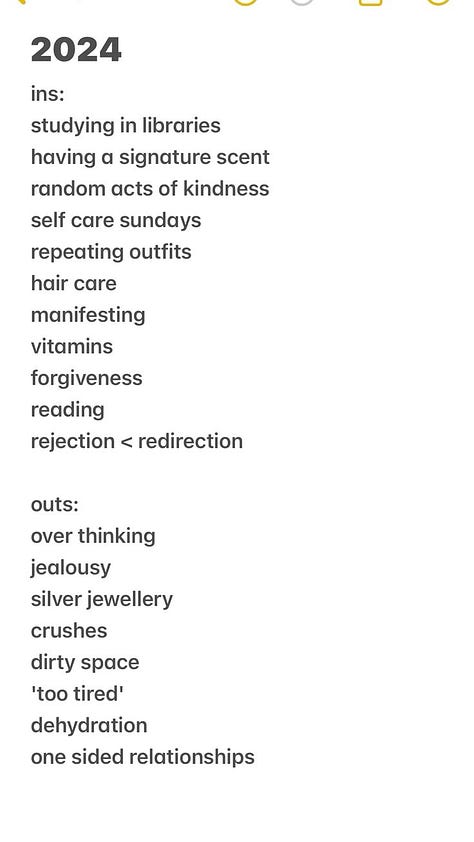

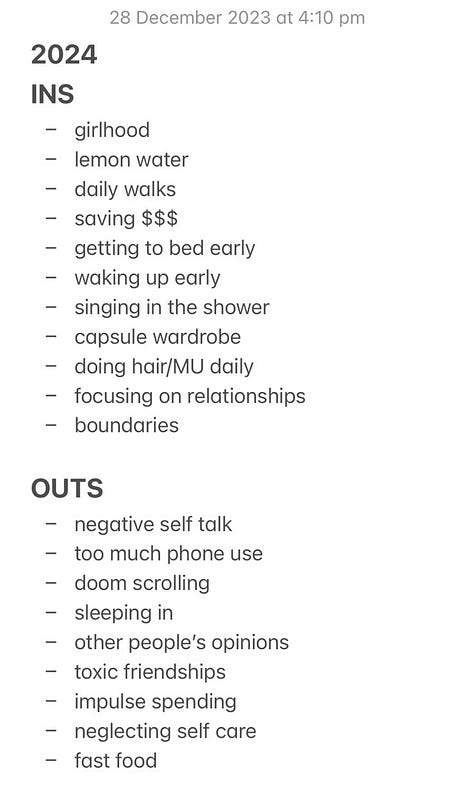

About eight weeks ago, it was impossible to open up TikTok or Instagram without seeing someone’s screenshotted list of what they were taking into 2024 and what they were leaving…out. The concept is so simple, I feel stupid explaining it. The parameters of what could be included were broad: some people listed out cultural phenomena, others stuck to vague personal-development concepts. The most successful examples combined the two, creating something midway between a vision board and a trend forecast.

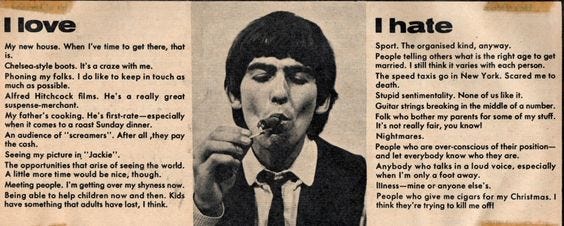

This format wasn’t new; it’s been a minor internet tradition for the last half-decade or so, and a mainstay of fashion and lifestyle media long before that. But this year, it was inescapable, completely dominating post-holidays discourse (at least on my side of the algorithm).

In-and-out lists are fascinating examples of how we telegraph identity online now: they’re public-facing yet intimate, earnest yet unserious, messy yet thoughtful. Most importantly, they’re funny! Saying we’re ditching oat milk with the no-further-questions finality of a high-powered magazine editor is a good bit.

But they’re a little deeper than a standard meme or personal branding exercise, right? They’re not New Year’s resolutions, but they come from the same emotional place – that tiny, often-overlooked chamber of the heart that yearns for something better.

I saw some articles wondering if these lists were a Zillennial replacement for the ‘classic’ resolution, and situated them within the ongoing backlash to the corporatized self-help culture that defined the 2010s. That rings true enough — these lists maintain a “new year, new me” spirit, but avoid the bootlicky shortcomings of their predecessor, which may forever be tainted by girlbosses and wide-eyed productivity YouTubers.

They don’t describe who the writer wants to be by the end of the year. Instead, they detail the world this person wants to exist in or build. Squint hard enough at any individual users’ list, and their values eventually show through. That’s a refreshing departure from the results-oriented, easily-abandoned New Year’s resolutions I tend to saddle myself with, and (perhaps!) a more effective one.

Since I gave a pedantic definition of the in/out list, I guess we also need to define that “classic” New Year’s resolution, too.

In his 1951 paper The New Year’s Resolution and Ascetic Protestantism (buckle up), sociologist Isidor Thorner points out that Americans tend to be a little…intense about their goals for the year.

Of course, many other cultures have annual traditions around reflection and atonement. Yom Kippur and Lent both hit on the same themes, albeit at different times of year. Historically, medieval knights supposedly re-committed to chivalry with something called a “peacock vow” at the end of the Christmas season. Ancient Romans sacrificed animals on January 1 to curry favor with the gods. According to multiple spammy articles, the Babylonians also had some holiday that involved returning borrowed farm tools.

That one was hard to verify, but the takeaway is clear: humans looooove to contemplate one year and dream up plans for the next. But the tendency to make those goals gigantic, expensive and lowkey impossible? That’s all-American, baby! Thorner attempted to figure out why.

He kind of gives it away in the title, but his answer is Protestantism. He defines the archetypal New Year’s resolution (which he abbreviates to NYR) as “a determination to control what are felt to be weaknesses of character,” which dovetails really well with the culture of emotional discipline (read: repression) and industriousness that was prized in colonial-era Protestant and Puritan communities. He remarks, kinda cheekily, that “the ascetic Protestant nature of the NYR is indicated by the fact that it is made – at least theoretically – for life.” He’s distinguishing this commitment to ongoing self-denial from more time-bound (and therefore achievable) periods of religious penance like Lent here. He also seems to be calling me out for every time I’ve meditated for three days in a row and called it a “lifestyle change.” Go off, Isidor, talk your shit!

Thorner attempts to prove this thesis by calling his friends in various countries to ask them if they’ve heard of New Year’s resolutions or plan to set them. He finds the countries with a historically Protestant influence (basically those that were once ruled by England – the US, Australia, Wales, South Africa, etc.) likely to engage in resolutions, while historically Catholic, Lutheran and Eastern Orthodox countries (Brazil, Spain, the USSR, etc.) either weren’t aware of the concept or only knew about it because of their freaky little Protestant neighbors.

The contrast leads Thorner to guess that the concept of the NYR wasn’t just an outgrowth of workaholic Protestant culture. By the end of the paper, he posits that the tradition was expressly spread by English-speaking churches in the 1700s. He’s particularly interested in John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Churches, who preached frequently about emotional control and addressing one’s own flaws. In 1742, Wesley started offering monthly all-night services to his congregation of rough-edged coal miners, which he pitched as a “godly alternative to spending their evenings in alehouses.”

These services were sometimes called “love feasts” (cute) and eventually drifted over to U.S. churches, some of which lined them up with ale-heavy holidays like New Year’s. Remember those middle-school dances that were supposed to keep tweens out of trouble, but just turned into a sickening mass of tangled Claire’s bracelets, Abercrombie labels and B.O.? Basically the same concept. With less grinding to Flo Rida. I assume.

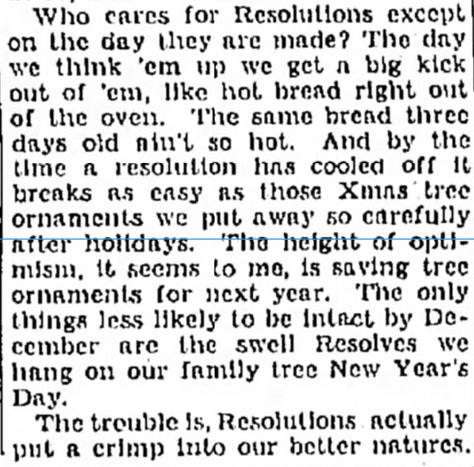

This tradition of solemn goal-setting bled into the secular sphere by the mid-19th century, where it became a consistent (if slightly divisive) annual custom. Turns out, hand-wringing about New Year’s resolutions is as old as the tradition itself. Take this little missive from 1908:

“Some say they do not believe in making resolutions on New Year’s day – that a good resolution need not wait until New Year’s day to be made. True. There is no fetich about the date. A good resolution is just as good a thing to make on December 1 as on January 1, provided you keep at it as well. But the making of good resolutions has become a sort of recognized New Year custom and a regular part of the day. It is a good custom, and we should be sorry to see it discontinued.”

Turns out “fetich” is an old-timey spelling of “fetish,” but we’re not going to get into that. The point is, the critiques of New Year’s resolutions’ essential arbitrariness have been consistent for at least the last century (see this example from 1916, this one from 1933, and this one from 1940).

Yet the tradition persisted. By the time Thorner was writing in the 1950s, it was an unquestioned part of American culture. The contents of these resolutions don’t seem to change much, either: according to Thorner, the most popular goals from 1947 included “save more money,” “go to church more often,” and (of course) “lose weight.”

Thorner is definitely not the most up-to-date thinker on the topic, but his definition of the classic, ascetic Protestant NYR is clarifying. These “original recipe” resolutions are defined by 1) a perceived weakness, and 2) an emphasis on effort or penance as the sole differentiator between success and failure.

Those two have carried through to the modern NYR – I definitely see shades of them in my half-filled journal spreads and Notion dashboards. In the 70+ years since Thorner wrote this paper, a third trait has come to join them: quantification. It’s no longer enough to say we simply want to go to church or hug our loved ones more; the tech-enabled McKinsey-fication of our personal lives means that numbers must be attached, too.

An over-reliance on quantification can put us at risk for what philosopher and game theorist C. Thi Nguyen terms “value collapse” – when the representations of an achievement (say, pages read or miles run) eclipse the values that led us to set those goals in the first place.

It can make the pursuit feel exhausting, and the achievement feel empty. Anyone who’s sped through a book they didn’t care about to hit a Goodreads goal or checked their Apple Watch one too many times on an afternoon walk knows what he’s getting at here. He also points out that if we’re not careful, the over-reliance on metrics can shrink our imaginative capacity, alienate us from our purpose and make the goals we set shallower and less fulfilling. Yikes! And if those goals were already coming from a Puritan sense of deficit, it’s really no wonder that the majority of resolution-makers don’t make it past January 10.

And yet. Even though I have so much evidence that New Year’s resolutions are weird and bad and bent toward failure, I am still moved by the near-universal drive to set them. Alex Olshonsky described this in a recent newsletter:

“As arbitrary as the Gregorian, or any, calendar may be, it fuels a collective momentum this time of year. The energy we create is undeniable. Annual rituals like these remind me that we are not just animals who hibernate in winter—we are the spark where the animal meets the mindful. We are not just bodies that instinctively rebuke the cold and seek shelter, we are thinkers whose minds constantly and unavoidably create something out of nothing.”

It’d be easier if we were all about rebuking the cold and seeking shelter, though, right? One of the most annoying things about being human is that once our primary needs are met, we insist on imagining something bigger. We’re a pathologically un-chill species. Our drive toward self-betterment and exploration is immensely powerful, and it can be abused or misplaced all too easily.

This year, I did my best to separate the worthy resolutions from the hyper-quantified, shame-based nightmares by asking myself a few simple questions: is this coming from a sense of weakness or a sense of hope? Is it something I want to fix within myself, or something I’m excited to see fulfilled?

These questions aren’t perfect; I still ended up in that paralyzing shame spiral described above. But the framing they encouraged kept me moving, at least. I did my best to keep my goals future-facing, and to focus more on a holistic vision of the future than on metrics of raw achievement. In other words, I basically made an in-and-out list.

These lists feel like a more trustworthy container for that “something created from nothing” which Olshonsky mentioned. They remind us that our dreams are not cudgels to beat ourselves with – they’re evidence of our essential dynamism and imagination, and deserve to be honored as such.

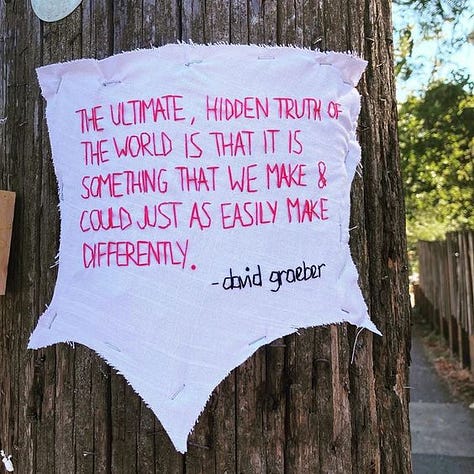

So, as I close out the month where dreams go to die and glance at the list of goals I’m already falling behind on, I’m trying to remind myself that change will happen whether I like it or not – the only thing that’s slightly within my control is the direction of that change.

I’m trying to remind myself that no behavior shift or habit can be built under perfect conditions. Curveballs will be thrown, jobs will be lost and gained, and relationships will build and decay. Resolutions, whatever form they take, will deform and mutate alongside changing circumstances. I’ll probably end the year looking less like a glowing vision board and more like the weird middle-figure on an Animorphs cover – somewhere between where I was and where I imagined myself to be. That’s okay. All I can focus on is taking the right actions, refining and aligning with a personal vision of an ideal future.

2023 was a bit of a shitstorm for me, but it showed me that change is much simpler than I want to admit. Not easier, but simpler. Ultimately, even the biggest transitions come down to a series of yeses and nos, ins and outs. Every decision gives me the option to advance or retreat from the world and life I want to build. That’s scary – and exciting.

This early part of the new year often feels like a shock to the system. The fluorescent ugliness of real life floods out the gentle-dancing candles lit on the darkest nights of winter.

Potential sours into regret, and time turns into lateness. The dignified possibility of January sinks into the past, replaced by February’s trampled-paper hearts and billboards for that fucking Bob Marley movie.

As spring begins and life speeds up, it becomes enticing to reject the fantasies nurtured when the year still felt new. To shove those dreams into a drawer. To blow out the candle because it is no longer the brightest thing in the room.

I am doing my best to resist that urge, and I hope, for your sake and mine, that you are too.